Making Geography Great Again.

A lesser point on the global neo-liberalism agenda is being reversed at astonishing speed.

Global neo-liberalism had the side consequence of making geography irrelevant. That may not have been an explicit part of the plan, but it was implied in the globalization of commerce and the digitization of everyday life. At a minimum, borders didn’t matter; to some extent, getting rid of them was the point. Call centers for US corporations in the Philippines and India were to be the height of fashion and efficiency.

To judge by the events of the past few years, but especially the past few weeks, the idea that traditional borders might disappear has not aged well. Quite the opposite. Find a globe, pull out an atlas. If you must, use a Mercator projection map. And grab some pins and some markers. Prepare to make a lot of changes.

Over the past few months, I’ve been working on an extended essay on Russia’s borders. In it I pointed out that Russia as a hegemon peaked geographically in 1914 and geo-politically in 1945, and has been declining and, specifically, territorially contracting ever since. I highlight Russia’s border vulnerability over the next few decades as its population and geo-political sway continue to diminish.

Examples of territories at risk include Kaliningrad, an isolated, non-contiguous forward military base picked up after World War II and now surrounded by NATO members. Along the immediate southern border, Russia is struggling to control Crimea, occupied since 2014. It too was non-contiguous to continental Russia until the construction of the Kerch Bridge in 2018 and then the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. There is also the enormous Russian Far East, taken from China by treaties in 1858 and 1860 when Russia was ascendant and China was not. That dynamic has since reversed. The Soviet Union and China skirmished over the border area as recently as 1969. You can be certain that the long-game playing Chinese have not forgotten about these lands. Further east are the southern Kurile islands claimed by Japan but occupied by Russia. There are other points of vulnerability in the far northwest of the country as well as its southern borders in the Caucasus and Central Asia.

In this context, Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008, Ukrainian Crimea and the Donbass in 2014, and Ukraine outright in 2022 are efforts not to expand, but to avoid contracting at an ever faster rate. That counter-intuitive notion, I argued, would be helpful to US policy makers and other third parties trying to understand Russia’s otherwise puzzling motivations.

But events have overtaken me. The incoming US president has expressed a desire to redraw the map of North America. His comments have shocked many, especially those in the US who, after 150 + years of settled borders domestically, may not be used to such notions. But for the rest of the world, revanchism and irredentism are not news. Borders are contested and move all the time.

So a quick refresher on the history of US borders is in order, particularly because as a relatively young hegemon, the US has only experienced expansion. That started in the middle of the 18th century when the English colonies had a narrow swath of land in northeast North America. Occupied by Native Americans and a handful of European trappers, traders, and settlers, the rest of the continent was claimed at various times by Spain, England, France, Canada (first France and then England), and later by Mexico and Russia.

What followed was a period of furious expansion, such that a mere century later, with the end of the Civil War in 1865 and the acquisition of Alaska from Russia in 1867, the current borders of the United States were largely set and have remained so for the past 150 + years. The Monroe Doctrine (1823) and Manifest Destiny (1845) were the pretty words used to explain and justify US expansion.

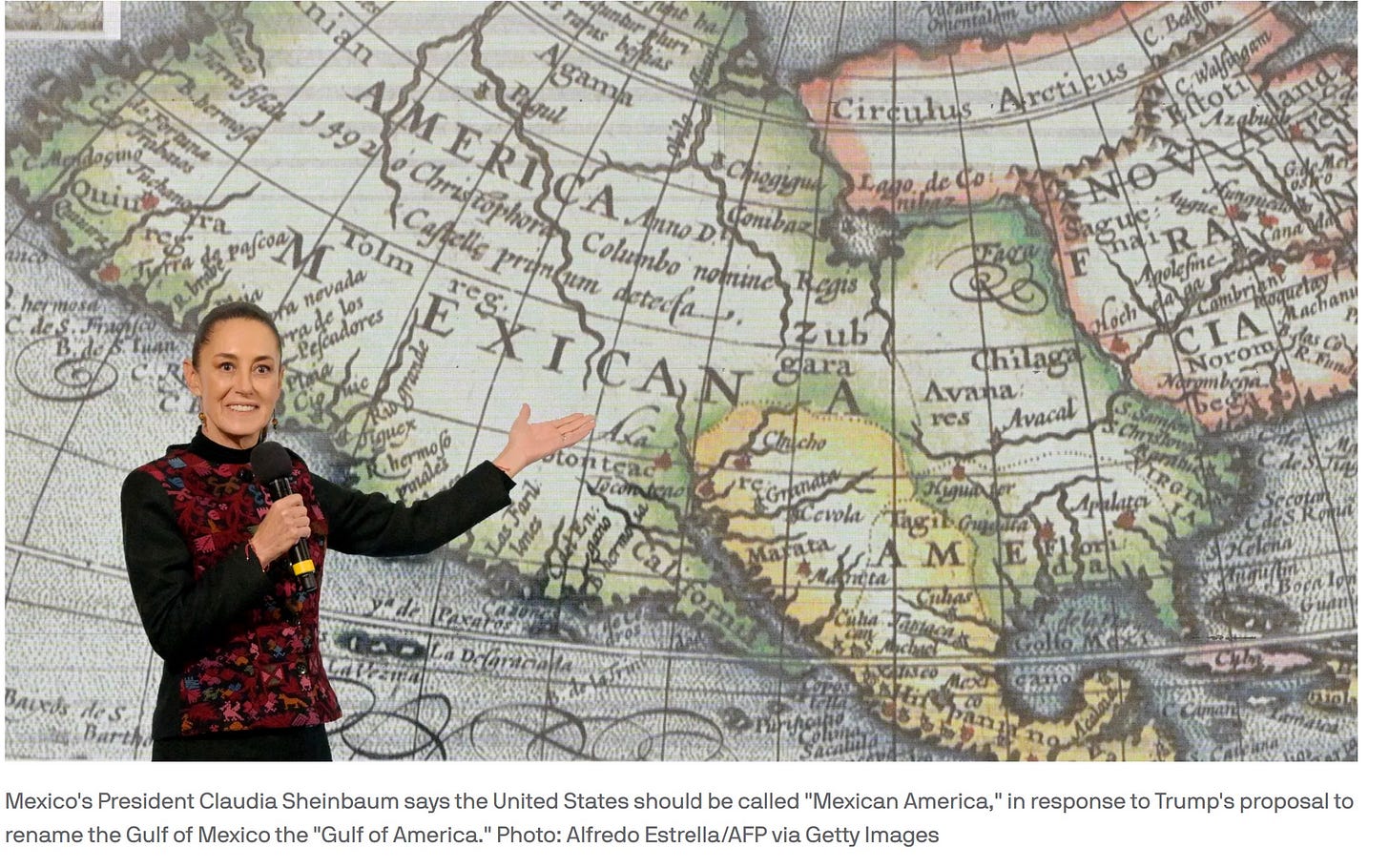

For reference, the current border with Canada along the 49th Parallel was settled by treaties in 1783, 1818, and the final Western portion in 1846. The current southern border is a product of the Mexican-American War in 1848 where Mexico ceded its northern territories—most of the current American West and Southwest—to the United States. (Texas had broken from Mexico and and joined the US a few years earlier, in 1845.) As a counterpoint, the President of Mexico recently appeared at a press conference with a map showing her country’s much larger pre-1848 borders.

Unlike the leading European powers, the US had few direct, non-contiguous, traditional colonies. The Philippines were the largest. It was taken from Spain (and the local population) in 1898 (until 1946) by the US in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War. (The US picked up Puerto Rico and Guam at the same time.) The US also used the Spanish-American War as an excuse to finalize its annexation of Hawaii, which it had forcefully taken over earlier in the 1890s. Late to traditional colonialism, the US extended its reach geo-politically and economically in a way that did not require full territorial control. Naval bases, airfields, and Coca-Cola would suffice. To a great extent—despite the loss in Vietnam in the 1970s and the retreat from Afghanistan more recently—this form of non-territorial hegemonic influence remains robust.

If our borders have been stable to the North and South, and natural to the East and West, many, many others are not. This is not in any way an exclusive list of potential near-term movements; these are just the largest ones (other than Russia) hiding in plain sight.

Greenland is all the rage. But please look at it on a globe, not a Mercator-projection. While it appears to be the size of Africa on a map, it is properly sized—about 1/14 the size of Africa—when seen on a sphere. The degree of Mercator distortion is greater the further the territory in question is from the equator. Greenland is far from the equator.

Kurdistan. Messieurs Sykes & Picot left the Kurds out the last time nation-states were being handed out, when the Ottoman Empire was collapsing during World War I. I doubt that the Kurds will be shy this time around about insisting on their own nation-state.

Korea. Reminiscent of East and West Germany. They existed as separate entities until they didn’t.

Kashmir. An unresolved matter dating from the partition of India in 1947, more than 75 years ago. Currently administered in part by India and Pakistan and China. Commingles local issues with the global geo-politics of India and China, the border between the two, and the fate of Tibet.

The Middle East in general where the borders are no more natural or settled than they were a century ago. (The term Middle East itself is from a Western perspective. Geography is embedded in our semantics. Re-read Edward Said. His Orientalism was insufferable the first time around, but is getting better with age.)

And many many more.

Indeed, unless there is a substantial natural barrier (wide river, tall mountain, deep sea) between two entities, it’s probably safe to assume that all nation-state borders have or can be contested.

But it is not just borders and who controls what. It is geography itself as a significant driver of global political economy. Great Britain’s prominence in the 18th and 19th centuries is simply inexplicable without repeated reference to its geography—a well-located and well-endowed island nation with a helpful moat separating it from all those warring continentals. The rise of the United States is no different: an even greater natural endowment and vastly larger east-west moat.

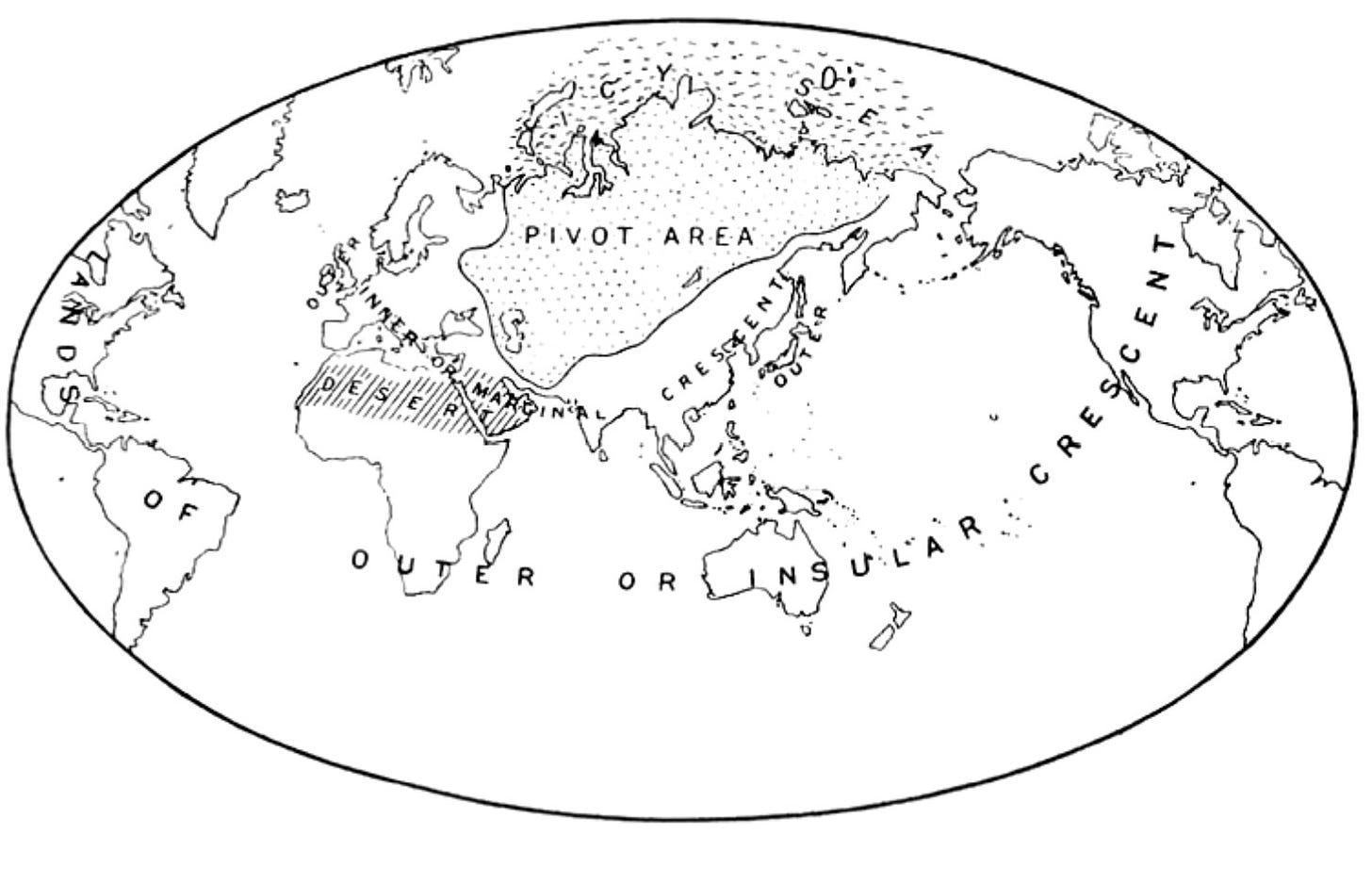

Trans-national ideologies and more recently technology were supposed to render geography irrelevant, but rivers, mountains, seas, and plains are making an analytical and practical comeback. The role of geography is now being championed directly within the DC Beltway by writers such as Hal Brands. The JHU scholar is reintroducing for a new generation the writings of Halford Mackinder, an English geographer and diplomat from early in the 20th century who emphasized the shift from naval power—popularized by the better-known Alfred Mahan—to control of the Eurasian Pivot Area or Heartland, at the time occupied by Russia and threatened by Germany. Mackinder proclaimed the end of external colonial expansion via naval power. The future, he argued, of geo-politics would be internally oriented on the Eurasian landmass.

For my own work on Russia, Mackinder makes essential reading. His writing coincides with the peak of Russia’s control of the Eurasian Heartland in 1914 or so, & not far from its geo-political peak in 1945. I argue that Russia has been struggling to control the Heartland ever since, with numerous buffer zones having been lost. Many of Mackinder specific points were challenged at the time and have not stood the test of time. But his importance is in reminding us that river drainages, mountain passes, arable land, navigable waters, inhospitable climates, etc. still matter. Mackinder making a comeback is perfectly consistent with the end of neo-globalism. Boundaries new and old are going up everywhere.

One development that Mackinder could not have foreseen is the opening up the Artic to year-round navigation due to global warming. That is the essentially on a par with creating new usable territories and pathways for the first time since the Age of Exploration. Greenland now matters a great deal more than just as a far northern (60-80 degrees North) ICBM early warning system from a prior age. Fun geographical fact from a similar latitude: Anchorage, Alaska (61.2 degrees North) remains a major cargo transfer hub, long past the time when long-range aircraft can go point-to-point almost anywhere on the globe. Why? Geography. Anchorage is roughly equidistant from key destinations in Europe, North America, and Asia.

With incumbents losing elections around the globe in 2024, and more aggressive nationalist leaders coming to the fore, the next several years suggest a slew of map changes coming. Keep your sharpies handy.

Comments welcome.

Great article! Peter Zeihan (with a lot of caveats) has also been talking a lot about the comeback of geography (and demography) as a relevant factor in the geopolitical stage. I have been leaning in on that theory for a while but seeing you write about this is gives it more weight.

How do you think this affects Southamerica? Particularly Argentina? It seems to that it has a great geography. But being far from everywhere didn't really help in a globalized world (also Argentinians have not helped much).

The stuff about Russia, China and Siberia is heavily phantasmic. Until the 1700s, the "Russian Empire" was the lands west of the Urals and a string of trading ports along the Arctic Circle around the corner to Vladivostok. Armed ships went upriver to buy furs, grain and livestock all summer long and then hunkered down to shiver through the winter. Until then, the Evenks, Samoyeds, and many other peoples of Eastern Siberia had generally never heard of China or Russia.

In the near future, China must annex Eastern Siberia for the same reason the US must annex Canada: Global Baking will render our current lands unable to feed our people.