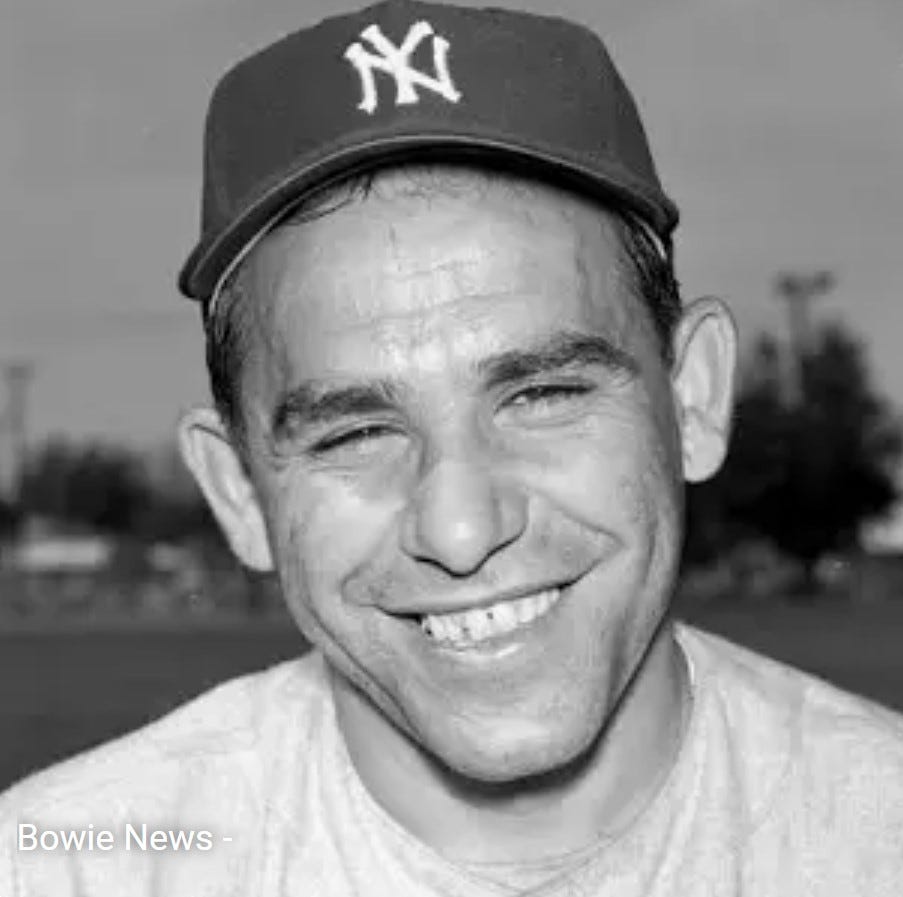

"It's tough to make predictions, especially about the future."

Yogi Berra on today's winner-take-all market frenzy.

As the calendar turns into a new year, my email box has been flooded by forecasts on how 2025 is going to play out: “target prices,” earnings growth, GDP, currency, etc. We know the current state of affairs. It’s the future that matters. So forecasts are a vital part of the stock-market eco system. But in this particular instance, it’s hard not to be struck by the winner-take-all frenzy dominating the US stock market. A handful of US technology companies have been driving the indices ever higher for the past several years, especially in 2024. The sell-side commentaries about these companies are nearly unanimous in their praise: Earnings and cashflow growth justify the lofty valuations… They are legal monopolies with huge moats... Management gets it… This cycle will last for decades, if not longer… One of the chip makers, I’ve been told by Wall Street brokers, has a unique combination of hardware and software that gives it a ten-year lead against all competitors. It can do no wrong.

Representing around 20% of S&P 500 Index company GAAP profits (2023) and approximately 30% or so of SP5 capitalization, these companies are generating an even higher share of Economic Value Added or other measures of profitability that take into account capital deployed and leverage. Based on these additional metrics, these leading issues should have even higher share prices… So goes the expectations narrative.

The dynamics of the US stock market the past few years have created a parallel and not unrelated disparity with Europe. Almost everyday brings another sell-side chart showing the widening differential between the US and Europe in regard to market cap, fund flows, P/E ratios, profit growth and whatever measure of sentiment or reality you choose. (Follow @MichaelAArouet on Twitter for all the gruesome details.) Those differentials are at multi-decade or all-time highs. These contrasts go are in turn reflected in geo-political narratives: The US has the AI mojo. Europe is the gang that can’t shoot straight. France is going down the financial and political drain. The German Wirtschaftswunder has been reversed. Mario Draghi and Ursula von der Leyen are out with recovery plans that acknowledge the extent of Europe’s weakness. The European Union itself is at risk. Perhaps Britain was not wrong, just early, about leaving.

So, what we’re observing is not just about an in-demand AI chip maker. It’s a grand winner-take-all paradigm across the board. And to judge by all of my emails, it is expected to continue.

What’s an investor to do as they review their portfolio at year-end? Near-term, the (market cap-weighted) index investor and momentum trader get to enjoy the ride. The growth investors who placed their markers on the right black and red velvet squares take a victory lap, claim prescience, and secretly wonder when to cash in their (literal) chips. The value investor can only watch and wait (as they have for the last several decades) for their opportunity.

It’s not exactly a great recipe for price discovery, for the few remaining people in the stock market who actually care about price discovery. For everyone else, it’s worth recalling that price discovery is the lost art of people coming together, expressing differing views on a topic and moving toward an acceptable if not always ideal agreement on the price of an asset. This natural process has been almost entirely eradicated in recent decades by passive investment structures, algorithmic and momentum strategies, and those quantitative products that have no fundamental component.

But I am one of those few market participants who still identify as a fundamental investor and care about price discovery. So even if what follows is just viewed as a classroom exercise, I think it’s important to go through the motions of treating the valuations of these market-leading securities from a fundamental perspective. The long-term horizon of my investment mandate allows that indulgence, as does my training as a historian.

The main issue for me is time. That is, what are the forecasts for these businesses through time? It’s not just how long before micro and macro mean reversion occur—the obvious outcome—but about the analytical assumptions behind the current frenzy. As Keynes wrote in his famous stock-market chapter of the General Theory—aptly titled, “The State of Long-Term Expectation”— our forecasts are a combination of what we can reasonably expect and how confident we are about the forecasts. While there is now a cottage industry in the academy on forecasting error, the current investor math goes well beyond it. The fundamental justification for the valuations of these companies is that business is going to be really good for as far as can be forecast. The present value of those future profits and cashflows—sadly, few if any actual dividends—comfortably justifies today’s share prices or better. That’s where the historian pauses: Those forecasts are generally extrapolations of current business lines. It is the continuation of the winner-take-all logic well into the future. That’s a problem.

To be a fundamental believer in the Mag 7+ (including two new late entrants—another chipmaker and a big data company) as investments today, from these levels on January 1, 2025, one has to be be convinced of one of two things. The first is that they going be the leaders in businesses a decade from now doing almost exactly what they are currently doing. Grab a sell-side report for one of your favorite Mag 7+. The components of the individual forecast are extensions of current business lines. They involve the usual suspects: size of addressable market, share of market, pricing, margins, all translating many years of rapidly escalating profits into a stunning Net Present Value. The companies have had a spectacular run, with extraordinary rates of the growth for at least five years, in some cases, a decade. The projections presume another decade of torrid expansion. Without it, the valuations just don’t hold up.

That is, the EV car company is forecast to continue to make EVs and its other existing business lines with greater and greater profitability throughout the forecast period. The software/services company’s outlook is the same: extension of its various current business lines, maintaining similar or better margins, even as revenue growth might slow down a bit. Same with the digital advertising revenue streams and the third-party computer hosting services. Each Magic Carpet Ride is forecast to continue to grow roughly in its current form at a high rate for an extended period of time.

For good reason, I haven’t seen a single sell-side report on one of these companies featuring a $50 billion, high-margin revenue line item in 2034 for a business “To Be Determined” at a later time. And I’ve yet to see one of these CEOs stand up and say, “we don’t really know what the next big thing is, but we’re sure to capitalize on it. Here is our expected revenue and profit from it.” No, they say they are going to continue doing what they are doing, just a lot more of it.

The problem with the continued exponential growth line of reasoning is that history suggests relatively few examples of it actually occurring. Growth yes; sustained nearly vertical growth in the same exact business line from a decade or two ago, no.

Current investors have a second option. And that is to believe that the management of the Mag 7+ will zig and zag over the next decade or two in just the way needed to catch the Next Big Thing. Again, the current activities of the Mag 7+ didn’t exist in this exact form a decade ago, and barely had their current form 20 years ago. (I exaggerate for effect, but you get my point.) So hats off to current management. They made markets, or guessed correctly, or reacted rapidly to get there. Congratulations.

This line of argument goes that if current management read the tea leaves correctly one time around, they can do it again. So investors may not know what the next big thing is, but they are comfortable that the leather-jacketed guy will figure it out for them. Same with the leader of the EV company. He’s working on a wide variety of business and non-business ventures. A different software CEO (not Mag 7+) is very explicit that he has figured out the Next Big Thing and is borrowing money and issuing shares to buy it all up.

But how many other CEOs have said that they have no idea how they’ll be making money ten years from now, and we should just trust them all the same? There’s nothing wrong with the close-your-eyes-and-count-on-the-CEO approach, if it is made explicit as part of the investment proposition. Warren Buffett’s investors have been doing it for decades. They simply trust the man, and with good reason. But one still has to ask whether the people who created today’s major markets or got lucky will be the same ones who will do it for the next decade or two?

So there are at least those two ways to view the Mag 7+ in a positive fundamental light. But it’s also not unreasonable to point out the somewhat long odds of either scenario working out just so. For instance, did today’s leaders have a clear path a decade ago that they have followed? Consider the current leader of the pack. Ten years ago, Nvidia’s 2014 annual report was about driving “visual computing” and being the “visual cortex of modern computers.” Artificial Intelligence is not mentioned once; there is a single reference to datacenters. (To be fair, references to artificial intelligence, AI, and datacenter/s pick up rapidly thereafter.)

The sell-side reports from the same time forecast continuation of the then modest trends, with an appropriate tinge of uncertainty. One from a major broker dated February 12, 2014 forecasts “modest topline growth (2-4% annual, excluding its indeterminable pipeline of new products.”) It continued, “We rate Nvidia Neutral. We like the company’s innovative technology in discrete graphics, workstations and mobile processors and its solid balance sheet and cash flow. However it faces a mature PC market which impacts discrete graphics sales, while the mobile processor business faces tough competition from Qualcomm, TI and others.” (ML, 2/12/14) Another report references “continuation of steady growth in its core gaming related GPU-segment, despite foreseeable headwinds…” That report suggests that Nvidia’s hardware risks becoming commoditized and that the future of the company is software. “NVDA remains a company in transition as the investment horizons need to be longer-term given the different ‘irons in the fire.’ It remains difficult to identify a catalyst in the near term that could change investors perception of the company.” (RBC, 2/12/14) A day later, a leading brokerage wrote that “We like the NVIDIA story, but see limited upside with high valuation, excluding cash and the Intel royalty.” (MS, 2/13/14)

So while the sell-side did not see AI coming, it does foresee it continuing. One recent report on the company has revenue increasing from $61 billion in fiscal 2024 to more than $270 billion in the year that ends January 31, 2027, with the company’s EBIT margin increasing (!!) to 70% and profits quintupling. (C, 11/21/24). That enthusiasm projected necessarily many years into the future is typical of sentiment around these stocks.

Were the current business models of the other Mag7+ foreseeable a decade ago? Not really. You can get dizzy following Apple’s zigs and zags. It is largely unrecognizable from the company it was 10, 20, or 30 years. Amazon finally started making money (rather than just getting larger) a few years ago when a background business needed for its primary retail operation moved into the foreground and took off. To be fair, Meta and Google are basically still in the advertising business and can be considered refutations of my argument. They’ve been growing at a torrid rate in the same line of business for years, though Google’s very successful Android gambit was not part of the original search picture.

Microsoft is probably the best example of closing your eyes and expecting more hyper-growth for decades to come. It has also zigged and zagged, made its share of mistakes, but is still basically in the software/systems/applications business. And it has continued to expand prodigiously. Bravo. All of those anecdotes about how much $1000 of MSFT shares from the 1986 IPO are now worth are legitimate assertions. But thousands of other companies did not have such skill or good fortune to navigate decades of rapid growth. Microsoft is the ultimate exception that proves the rule that nearly vertical growth expectations in unchanging lines of business don’t usually work out.

This is not to suggest that discrete businesses can’t be successful over long periods of time. There are lots of century-old companies available for investment, but they do not come with Mag 7+ lofty valuations and expectations. Exxon is still in same line of business, with allowance for forecastable industry technology and macro-economic evolution, that it was a century ago. And one might have said in 1925 that based on population and consumption trends, Standard Oil of New Jersey is a good investment over a long period of time. But even in this case, Exxon’s growth has been of the steady rather than explosive sort. And given the move away from carbon in recent years, forecasting another century of carbon-based growth may be a mistake.

The same is roughly true with some pharma companies like Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and the utilities. They’ve grown steadily—but not exponentially—with population, economies and technology, but are basically in the same business that they were fifty years ago. Many of the Nifty 50 from the late 1960s are still here today and still recognizable from their prior forms, but they are far from the market leaders that they once were.

One might expect these Old Economy stalwarts to be in the same line of business decades from now, but you just don’t know. Disruption lurks behind every corner. Even these survivor companies have pivoted in ways that their founders and original backers likely did not imagine. Take Coca-Cola. It’s original deliverable was at a pharmacy fountain. The earliest company leaders thought so little of the off-premise business that they literally gave away the bottling licenses in perpetuity. When was the last time you walked down to the corner drug store after classes were over, jumped on the swivel-stool, and asked the soda-jerk for a refreshing Coca-Cola for you and your date?

Sam Walton didn’t sell groceries. Wal-Mart’s big pivot in 1988 was to move into the grocery business. It worked; it is now the largest grocer in the nation. But it was not in the forecast in the years prior. The phone companies managed the transition from wireline to wireless. In retrospect, that now appears to have been seamless, but at the time, it was not clear how it was going to work out.

Or consider those market dominating set-it-and-forget-it high-growth companies from yesteryear that didn’t make it at all: Nokia, Eastman Kodak, Blackberry, Avon, etc are all within recent memory. Go even further back and you can find market leaders who could do no wrong, until they changed or the world changed on them: The Pennsylvania Railroad, US Steel, and GM, to name just a few. Search the internet for the market leading companies every decade from the past century. You get my point. They did not get the pivot right.

So given this canvas of often rapid business change, how does one seriously forecast future cashflows for a company? It’s a fair (and necessary) question. In my dayjob, I have the luxury of a narrow investment mandate—a high and rising income stream—that involves generally stable, modestly growing enterprises. Yes, their business models evolve over time, and can change abruptly, but in general their cashflows can be reasonably forecast for around 5 years. That time horizon is not too much to question believability, but not too short as to be useless. It is a compromise with the ravages of father time. Basic diversification covers those instances where I or the company get it wrong.

No doubt the rewards of getting a 50% long-term annual growth forecast correct—either as an investor of a company executive—are vastly superior to the more meagre benefits of getting a 5% trajectory right. But as are the rewards, so are the risks. Heading into 2025, the market seems to be pricing in continuation of the “winners-take-all” taking all. While I wish my growth and momentum friends boundless expansion in 2025 and beyond, it’s far from certain that it will come from the same companies that have generated those results in the past, or in the same lines of business.

I’m happy to crowdsource examples that confirm or contradict this analysis. Please send them in.

Image courtesy: The Bowie News https://bowienewsonline.com/2016/11/yogi-berra-is-the-al-mvp/

As a professional historian operating "under cover" here, I very much appreciated this. The industry seems to me to be terrifically bad at weighing continuity and change, which I suppose isn't a surprise: it isn't part of the training.

Great article. The more growth you price in and longer your time horizon, the wider your range of possible outcomes needs to be - both to the upside and to the downside.

Investors are very optimistic around the top companies right now. Some of that is probably warranted, but I can't help but wonder if Nvidia is planting the seeds of its own destruction.

Assuming they keep their pricing power for any length of time, does the cost of the chips required to run AI make it impossible to make money from AI?

OpenAI recently said that at $200/month for each user, it still loses money on the pro plan. People will use AI for free, and they'll pay $20 a month for it, but there's no proof that enough people are willing to pay enough money to make OpenAI profitable.

Nvidia is basically dependent on a handful of companies to keep buying GPUs hand over fist for AI development. How long will investors allow them to keep piling money into a technology that doesn't look like it'll make actual profits any time soon?

History is full of new technologies that changed the world, but lost early investors piles of money: canals, railroads, the internet, the over-investment in fiber optic cables in the early 2000's...

I could be totally wrong, but I haven't seen much discussion around that sort of possibility.